As organisations respond to the forces of globalisation, they are expanding beyond their local markets into international markets as multinational corporations (MNC’s) (Deresky, 2017). In a highly competitive international market, organisations are seeking the best team members to compete effectively and efficiently, regardless of their nationality (Mustajbašić & Husaković, 2016). Consequently, traditionally homogenous teams have evolved into culturally diverse teams across nations and in the virtual sphere. Subsequently, knowledge transfer and team synergy are interrupted by barriers arising from members’ heterogenous cultural beliefs, behaviours, cognition and values (Cagiltay, Kaplan & Bichelmeyer, 2015). Aside from these barriers, multicultural teams are exceedingly desirable for their diverse perspectives, skill sets and creativity which leads to greater innovation and problem solving if managed effectively (Deresky, 2017). It is the manager’s responsibility to effectively motivate and lead these diverse teams towards achieving organisational goals. This research paper serves as a tool to inform managers of cultural diversity, what motivates various cultures and how they can lead effective, efficient and highly productive multicultural teams.

A team is a group of two or more individuals whose work is interdependent on another’s to achieve a shared goal (Robbins & Coulter, 2016). According to Robbins and Coulter (2016), an organisation’s culture dictates the roles and norms that team members are expected to follow. Mockaitis, Zander and De Cieri (2018) explain that, in their elected roles, managers exhibit specific behaviour that leads their team to success. Additionally, managers inform their team members of the expectations (norms) they have towards the members’ loyalty, efforts and performances (Deresky, 2017). Knein, Greven, Bendig and Brettel (2020) posit, a team must conform and collaborate their efforts to meet its goals. Therefore a team’s goals must align with the organisation’s goals to promote cohesion and productivity (Deresky, 2017). However, a barrier to this conformity and unity is the socio-cultural context of the team members (Cagiltay, Kaplan & Bichelmeyer, 2015). This, being their national cultures and subsequent dissimilarities which extends the differences between countries’ cultures, also known as cultural distance (Boscari, Bortolotti, Netland & Rich, 2018).

National cultures are the value systems and attitudes that are shared by a group of people from a specific country that shapes their social norms, behaviours, expectations and understandings which distinguishes them from other cultures (Erciyes, 2019). This point is challenged by Beugelsdijk, Kostova and Roth (2016) whereby they state that culture does not only originate from a country but rather from different regions, generations, social groups and socioeconomic groups. Disadvantages of multicultural teams include issues surrounding stereotypes, communication issues and mistrust between team members, however, these multicultural teams also present the organisation with a greater diversity of ideas, restricted groupthink and an increased attention spent on understanding others’ perspectives (Robbins & Coulter, 2016).

Nonetheless, fundamentally, ‘national’ culture shapes peoples’ behaviours and beliefs of what is important (Robbins & Coulter, 2016; Knein et. al, 2020). Furthermore, Khan and Law (p. 37, 2018) contend national culture influences how people interpret, evaluate and understand concepts and communication because it “shapes their customs, ideas, habits, traditions, language, and shared systems of attitudes and feelings”. Finally, this will influence how individuals solve problems, make decisions, communicate and orient themselves towards tasks or relationships (Deresky, 2017). Cultural intelligence, which is an individual’s skills and ability to be aware of, relate to and be sensitive towards other cultures’ needs, values and behaviours (Robbins & Coulter, 2016).

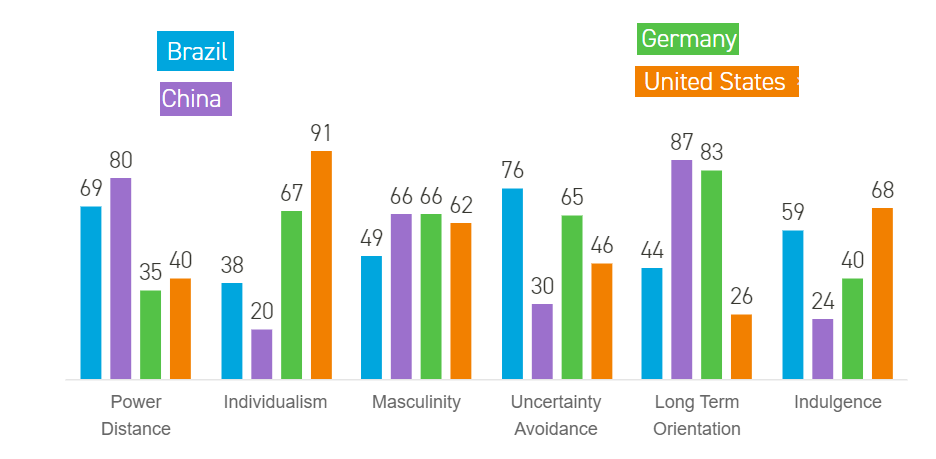

In 1980, Gert Hofstede created a framework which conceptualises the relationship between a country’s national culture and their values (Beugelsdijk et. al, 2016). Five independent dimensions show how the country’s culture impacts its citizens’ behaviours. They are as follows:

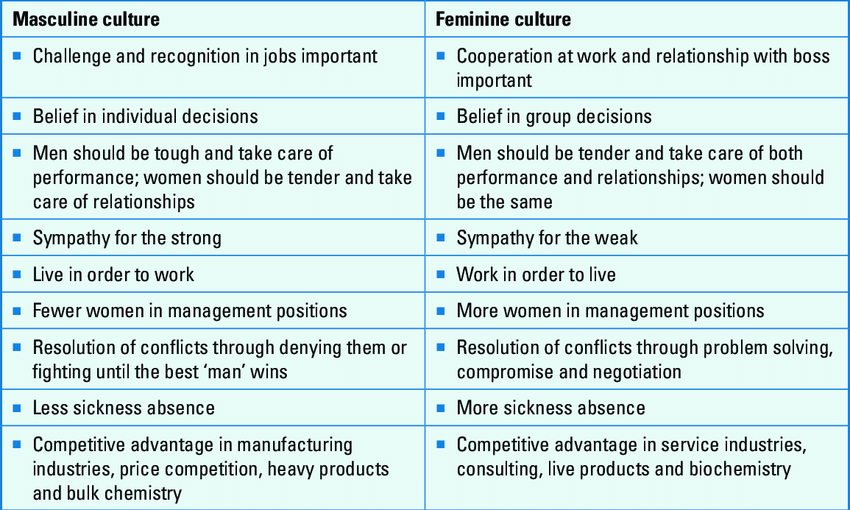

Power distance (PD) regards how a culture distributes power amongst its people, therefore it also pertains to equality and authority (Hollenback, Gerhart & Wright, 2018). Additionally, uncertainty avoidance (UA) concerns how threatened people are by ambiguous future situations (Erciyes, 2019). Moreover, individualism-collectivism expresses the strength of the relationship between an individual and others in a culture (Hollenback et. al, 2018). Furthermore, masculine cultures value achievement, competition and assertion whereas feminine cultures value relationships, fairness and the wellbeing of people and the environment (Deresky, 2017). Lastly, long term orientation versus short term orientation indicates whether cultures look to the future, value saving and are persistent or if they are short term oriented and focus on values and traditions of the past (Hollenback et. al, 2018).

Besides Hofstede’s Framework, in 2004 the Global Leadership and Organisational Behaviour Effectiveness program was established to supplement Hofstede’s dimensions and managers’ knowledge on identifying and managing cultural differences (Robbins & Coulter, 2016). Out of the nine dimensions, three new dimensions were identified; gender-differentiation, in-group collectivism, and performance orientation (Robbins & Coulter, 2016). Robbins and Coulter (2016) state, gender differentiation examines how much society enables women to be in decision making and leadership roles. Additionally, Deresky (2017) defines in-group collectivism as the degree to which individuals take pride in their belonging to social and professional groups. Finally Robbins and Coulter (2016) describe the performance orientation dimension as the extent to which a culture uplifts and honours group members for excellent improvement and performance.

Whilst some individuals will want to strictly abide by their norms and values in a ‘tight culture’, others will be more conforming and not abide as strictly to their norms and values in their ‘loose culture’ (Deresky, 2017). It is a manager’s prerogative to understand, manage and leverage their employees’ needs, goals, values and expectations to effectively lead and motivate them.

Motivation is a psychological process that results in goal or performance directed behaviour that satisfies human needs (Cook & Artino, 2016). According to Maslow in Deresky (2017), needs are a feeling of deficit. Cook and Artino (2016) declare intrinsic motivation originates from an individual’s desire to do an activity for its innate satisfaction such as curiosity and pleasure; whereas extrinsic motivation, entails external rewards and punishments which directs an individual to perform the appropriate behaviour.

Mustajbašić and Husaković (2016) have identified the following: employees from a high PD culture are motivated by hierarchy, security status whilst employees from a low PD culture are motivated by teamwork. Additionally, employees from a high UA are motivated by stability in their positions whilst those in low UA cultures are motivated by unfamiliar risks. Besides this, employees from a more individualist culture are motivated by competition whilst those from a more collective culture are motivated by friendship and collaboration. Moreover, employees from a masculine culture are motivated by rigid structures and long-term orientation whereas employees from feminine cultures are more motivated by a short-term orientation with less restrictions in their role.

In the opinion of Alghazo and Al-Anazi (2016), managers must aim to create an environment that is conducive to improve employee performance. Firstly, management should query which of their employees’ needs are satisfied through working, this is known as the meaning of work (Deresky, 2017). The general need that drives people to work is for an income (Sharabi, 2017). However employees also work out of interest, to make contact with others, to serve society, to keep occupied, and to earn status and prestige (Zhao & Pan, 2017). What determines their importance is what individuals value as well as the economic stability of the country they are working in (Deresky, 2017; Sharabi, 2017). Additionally, managers should consider employees’ work centralities, which is the relative importance work poses to people in comparison to leisure, community, religion and family differs between cultures (Khan & Panarina, 2018).

According to Fiaz, Qin, Ikram and Saqib (2017) there are two kinds of motivation theories. Firstly need-oriented motivation stipulates, individuals are driven to satisfy their needs (Badubi, 2017). Whereas process-oriented motivation asserts that individuals’ behaviours are started, directed and stopped through the inclusion or exclusion of variables which either punish or reinforce a behaviour (Badubi, 2017).

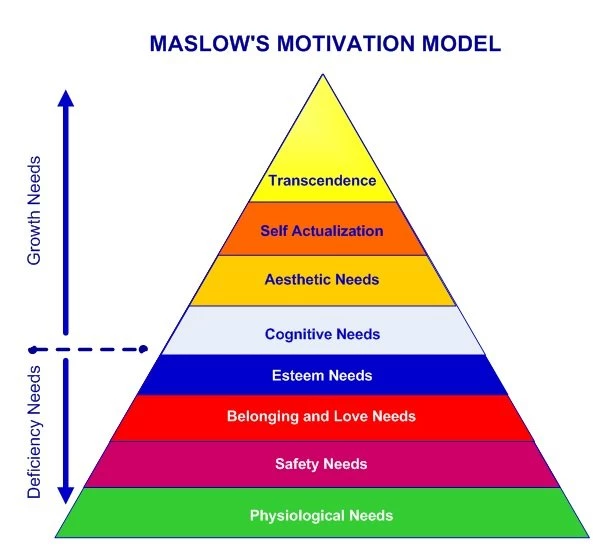

Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs in Robbins and Coulter (2016) proposed that every individual, regardless of culture, has five levels of needs. In his need-oriented model, Maslow progresses from physiological needs, to security needs protection from emotional and physical harm, thereafter social needs such as affection, friendship and belongingness, subsequently esteem like autonomy, achievement and recognition follow and finally self actualisation needs like growth, potential and self-fulfillment. Once a lower-level need is met, people progress to higher level needs (Badubi, 2017).

Moreover, McClelland’s Human Motivation theory addresses individuals’ needs for power, affiliation and achievement. According to Erciyes (2019), individuals with the need for achievement will take moderate risks and work hard under any conditions. Furthermore, people in need of power will take the greatest risks and have a desire to control functions in the team (Erciyes, 2019). Finally, individuals with the need for affiliation desire stronger interpersonal relationships and fear rejection from others within their network.

Besides, Herzberg’s two factor model, known as the motivation-hygiene theory proposes that employees’ intrinsic motivation is attached to job satisfaction whilst extrinsic factors create job dissatisfaction (Robbins and Coulter, 2016). Herzberg proposed that managers should amplify achievement, recognition, advancement and responsibility to motivate their employees (Deresky, 2017). Whereas Herzberg recommended improving extrinsic factors like an employee’s salary, company policies, working conditions and job security to avoid dissatisfaction amongst employees (Hollenback et. al, 2018).

What’s more, the Goal Setting Theory indicates that employees which accept and work towards a defined goal are more motivated (Robbins and Coulter, 2017). Employees are driven towards performance goals, learning goals or behavioural goals. Self-efficacy also determines if a goal is achieved because if employees believe they have the capability to achieve the goal, they will pursue it more (Schmidt, 2019).

Furthermore, a process-oriented motivational theory like B.F. Skinner’s Reinforcement Theory contends that all behaviour has consequences (Deresky, 2017). Desirable behaviours that result in rewards will be repeated, whilst behaviour that is unrewarded or punished will be less likely to be repeated (Robbins and Coulter, 2016). In addition, Edgar Schein’s model of Leadership and Culture proposes that managers’ basic assumptions construct the values of the team, which later form the practices and behaviour of a team, thereafter, creating the culture of a team. According to Schein, leadership and culture are inseparable as the leaders form the teams’ artefacts such as team construct and the language used; its values and its basic assumptions of how the team should operate (Erciyes, 2019).

Managers use monetary and non-monetary tools to influence employees’ behaviours and create a final goal for employees to achieve. As employees move from basic needs to higher level needs, their source of motivation becomes more intrinsic than extrinsic (Robbins & Coulter, 2016). Firstly, managers could use monetary tools like staff discounts, rent subsidies, bonuses, long-term contracts and other employee fringe benefits to motivate staff extrinsically (Erciyes, 2019).

Secondly, they could employ a plethora of non-monetary tools such as status, job content, career progression and belonging to professional groups to motivate staff intrinsically (Deresky, 2017). Besides, Cagiltay et. al (2015) recommend the promotion of valence, self-efficacy, trust and instrumentality amongst virtual team members. Moreover, Zhao and Pan (2017) recommend increased communication amongst managers and their subordinates, providing staff with greater power and recognising individual achievements to further motivate employees.

Whilst it is vital to comprehend the multicultural workforces’ unique values, In Ericyes (2019), 93% of the respondents claimed that their nationality did not influence their motivation. Instead this group reported that their managers and subsequent leadership style their style a greater impact on their motivation. In fact, Alghazo and Al-Ananzi (2016), Deresky (2017) and Erciyes (2019) claim that managers are the most appropriate implementers of motivational methods and found a strong correlation between leadership and motivation.

Whilst a company’s culture is standardised, managers will need to adapt their leadership styles to effectively motivate specific employees depending on their personal requirements. According to Deresky (2017), managers must inspire and influence the thoughts and behaviours of their employees around the world.

Firstly, leaders must exhibit cultural awareness, cultural sensitivity and adopt a global mindset to be effective in multicultural teams (Robbins and Coulter, 2016). This global mindset consists of intellectual capital, psychological capital and social capital. Robbins and Coulter (2016) define intellectual capital pertains as a manager’s knowledge of how international business is conducted on a global scale. They state, psychological capital involves a manager’s willingness to be open to new experiences and thoughts. Finally, social capital is a manager’s ability to configure relationships and trust with others of diverse backgrounds (Robbins and Coulter, 2016).

In 2019, Erciyes established that managers utilise different types of power in varying leadership styles to motivate employees. Firstly, hard power is utilised in a more hierarchical structure whereby employees are pressured and given an ultimatum to meet a goal (Erciyes, 2019). Whereas soft power utilises persuasion to get employees to do what they manager wants but leverages the employees’ intrinsic motivations to achieve a goal. Managers will utilise various control mechanisms and delegate power differently according to the task at hand, the company culture and what employees’ value.

Fiaz et. al (2017) investigated leadership within a bureaucratic company in Pakistan and found that autocratic leadership has a negative impact on employee motivation, whilst laissez faire leadership and democratic leadership had a positive impact on employee motivation. Thereby, employees felt more motivated when they were controlled less, and they could participate more in the decision-making process.

In autocratic leadership there is a high power distance between the manager and their subordinates, team members’ behaviours are work centered and they are driven to be highly productive (Alghazo and Al-Anazi, 2016). Contrary to this, Hollenback et. al (2018) state democratic leadership and Laissez faire leadership, employees have greater control, influence and authority over the work being done.

Correspondingly, Alghazo and Al-Anazi (2016), identified that transactional leadership correlates with extrinsic motivational factors, whilst transformational leadership correlates with intrinsic motivational factors. Transactional leaders are outcome oriented and have a work centered focus whereas transformational leaders are more motivational, process oriented and use a work centered and people centered approach (Alghazo & Al-Anazi, 2016). During times of difficulty in managing a multicultural team Deresky, (2017) recommends that managers; acknowledge cultural gaps, intervene in the team’s structure if there is conflict, conduct managerial intervention by setting the norms of the team early and if the team’s dynamics are still conflicting it would be best to remove a team member from their post.

To build and manage multicultural teams effectively, managers should implement the ‘SPLIT’ framework as stipulated by the Harvard Business School (2019). Firstly, managers should consider the team structure, and how it impacts distribution of power. To induce a more collaborative and productive team, managers can create shared goals in the team. Additionally, managers should consider the process in which the team communicates, builds trust and disagrees. Thereafter, managers should be mindful of the language used in the team and encourage non-native English speakers to participate. Accordingly, managers must encourage team members to learn about each other’s identities and cultural differences to promote cohesion and collaboration. Finally managers must consider what technology facilitates effective and efficient team operations and employ it.

The former literature review exhibited the key elements of this research paper, these include culture, multicultural teams, cultural dimensions, theories of motivation, tools for motivation and leadership styles. The following discussion will provide managers with realistic scenarios, relevant theories and practical solutions to managing multicultural teams.

In teams where there is a low PD, employees are motivated by teamwork whereas in teams where there is a high PD managers are more authoritative figures and incentivise employees to work (Zhao & Pan, 2017; Erciyes, 2019). According to Robbins and Coulter (2016) and Khan and Panarina (2018), Sweden and the United States of America are countries with a low power distance. Whereas France, Mexico and Singapore are more hierarchical societies and thus have a higher power distance (Robbins & Coulter, 2016).

Americans and Swedes would be motivated by democratic leaders and motivational factors such as being given autonomy over their work and having less bureaucracy in the working environment. Whereas the French, Mexicans and Singaporeans would be incentivised by the bonuses and subsidies offered by their autocratic leaders. The latter would work in a more hierarchical structure whereas the former would enjoy a more equal distribution of power in a collaborative team.

Additionally, in Italy, Mexico, France, Russia and Pakistan the culture is permeated with high UA, as people are anxious about job security, need more time to plan and are not big risk takers (Khan & Panarine, 2018). Contrarily, employees with a low UA in countries like Canada, the United States of America and Singapore will be comfortable with rapid changes (Zhao & Pan, 2017). Employees with a low UA can be motivated by opportunities for rapid change, promotion and taking risks. Whereas the employees with high UA would be motivated by managers which ensure them of their career’s security. Additionally, these low-risk takers would want more control held by their superiors and their superiors would most likely incentivise their work through coercive power.

Besides this, employees from Australia, with a high individualistic outlook are more motivated by autonomy and opportunities for their own gain whereas employees from a collectivist culture like that of South Africa are more motivated by team goals and team support (Hofstede Insights, 2020).

Moreover, employees that are short term oriented, like the Japanese and Chinese care more about traditions and events from the past. They will be motivated by leaders who provide them with immediate gratification and uphold the organisation’s traditional values and expectations for employee performances. Contrary to this, long term-oriented employees from Australia, Germany and Canada are more concerned about future learning opportunities and promotions (Robbins & Coulter, 2016).

Then again, employees from a masculine culture like Australia will follow traditional roles and compete with each other, whereas employees from a feminine culture, like Sweden will be more flexible in their roles (Zhao & Pan, 2017). Employees from the masculine cultures will be motivated by competition, promotions, self-fulfillment and monetary benefits whereas employees from feminine cultures are more motivated by relationships and building team spirit.

Finally, when considering the GLOBE project’s gender differentiation, Egypt was one of the highest rated countries for maximising gender differentiation in comparison to Slovenia which had a much lower discrimination between genders (Robbins & Coulter, 2016).

Additionally, the Chinese were found to have a high rating for-in-group collectivism whereas New Zealanders had a much lower rating. Nevertheless, New Zealanders scored high on the performance orientation dimension which contrasted greatly with Argentina’s lack of societal encouragement.

This research paper serves as a gauge for managers to measure their understanding of the concepts related to multicultural teams. These concepts included teamwork, Hofstede and the GLOBE project’s cultural dimensions. From this, managers can use this paper as a framework to identify and categorise employees’ values, attitudes and behaviours from countries around the world. Furthermore, several need-oriented and process-oriented motivational theories were described, consequently managers can use this paper to design motivational strategies depending on their team’s goals and employees’ individual values.

Thereafter, it is established that managers need to decide on what leadership style will be appropriate to motivate and guide a productive, collaborative and efficient team. Consequently, autocratic teams, led by transactional leaders are more effective for time constrained, riskier tasks. Subsequently, democratic and laissez faire teams paired with transformational leaders distributed more power to employees and created highly engaged employees that achieved higher order needs like esteem and self actualisation.

Finally, this research paper combined information from the literature review and contextualised it with examples from the cultures of a plethora of countries around the world which are accumulating in the global workforce.

References:

Badubi, R, M. (2017). Theories of Motivation and Their Application

in Organizations: A Risk Analysis. International Journal of Innovation and Economic Development 3(3), 44-51. http://dx.doi.org/10.18775/ijied.1849-7551-7020.2015.33.2004

Beugelsdijk, S., Kostova, T., & Roth, K. (2016). An overview of Hofstede-inspired

country-level culture research in international business since 2006. Journal of International Business Studies 48, 30-47. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-016-0038-8

Boscari, S., Bortolotti, T., Netland, T, H., & Rich, N. (2018). National culture and operations management: a structured literature review. International Journal of Production Research, 56(18), 6314 – 6331. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2018.1461275

Cagiltay, K., Kaplan, G., & Bichelmeyer, B. (2015). Working with multicultural virtual teams: critical factors for facilitation, satisfaction and success. Smart Learning Environments, 2(11), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-015-0018-7

Cook, D, A., & Artino Jr, A, R, A. (2016). Motivation to learn: an overview of contemporary theories. Medical Education, 50, 997–1014. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13074

Deresky, H. (2017). International Management: Managing Across Borders and Cultures. (9th Edition). Harlow, England: Pearson Education Limited.

Erciyes, E. (2019). A New Theoretical Framework for Multicultural Workforce Motivation in the Context of International Organizations. SAGE OPEN 9(3), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019864199

Harvard Business School. (2019). Managing Global Teams. Retrieved from: https://www.library.hbs.edu/content/download/69471/file/Managing%20Global%20Teams.pdf

Hofstede Insights. (2020). Country comparison. Retrieved from: https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/australia,japan,south-africa/

Khan, M, A., &. Panarina, E. (2018). The Role of National Cultures in Shaping the Corporate Management Cultures: A Four Country Theoretical Analysis. Journal of Eastern European and Central Asian Research 4(1), 1-25. http://dx.doi.org/10.15549/jeecar.v4i1.152

Knein, E., Greven, A., Bendig, D., & Brettel, M. (2020). Culture and cross-functional coopetition: The interplay of organizational and national culture. Journal of International Management 26(2), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2019.100731

Mockaitis, A, I., Zander, L., De Cieri, H. (2018). The benefits of global teams for international organizations: HR implications, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(14), 2137-2158. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2018.1428722

Mustajbašić, E., & Husaković, D. (2016). Impact of Culture on Work Motivation: Case of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Journal of Business & Economic Policy, 3(3), 79-87. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23281662

Noe, R, A., Hollenbeck, J, R., Gerhart, B., & Wright, P, M. (2018). Fundamentals of Human Resource Management. (7th Edition). New York: USA: McGraw-Hill Education.

Robbins, S, P., & Coulter, M. (2016). Management. (13th Edition). Harlow, England: Pearson Education Limited.

Schmidt, G. (2019). The need for goal-setting theory and motivation constructs in Lean management. Industrial and Organizational Psychology 12(3). DOI: 10.1017/iop.2019.48.

Sharabi, M. (2016). The meaning of work dimensions according to organizational status: does gender matter? Employee Relations 39 (5), 643-659. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-04-2016-0087

Zhao, B., & Pan, Y. (2017). Cross-Cultural Employee Motivation in International Companies. Journal of Human Resource and Sustainability Studies 5(4), 215-222. https://doi.org/10.4236/jhrss.2017.54019